“A writer wastes nothing,” a saying that’s attributed to F. Scott Fitzgerald, may not be true for all writers, but it’s true for me. It’s especially pertinent to my new standalone novel, The Night Visitor, which goes on sale today. It’s a tale of love, murder, corrosive family secrets, and the inexplicable mysteries of the human heart and mind. It was inspired by a tragic period in my life.

The protagonist of The Night Visitor is Rory Langtry, a young socialite and business executive, who may have murdered her twin sister and shot her fiancé, Junior Lara, making it look a murder/suicide. Junior survived but has been minimally conscious and in a hospital subacute unit for years. He’s still accused of murdering Rory’s sister. While Rory has gone on with her life, Junior’s family maintains that she’s the shooter, protected from justice by her wealthy family.

As Junior finally nears death, Rory begins to have inexplicable visions and sensations—some terrifying, some wonderful—of things that only Junior could know and feel. She comes to the frightening conclusion that Junior has opened a mind/body connection with her and she’s doomed to die with him unless she can find a way out. Has Junior attached himself to Rory as a way of enlisting her help to find the real murderer before he dies or is Rory, consumed by guilt, losing her mind?

So, what prompted me to make a minimally conscious man a major character in a book? The short answer is: I know Junior’s world and its unique heartaches because something similar happened to my father and I felt compelled to tell the story.

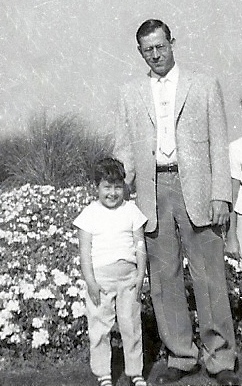

Some years ago, after a series of strokes, my seventy-eight-year-old father fell into a coma. After a few weeks, he woke up, as such patients usually do. However, how much was left of his mind was a point of contention between my family members, just as it was among the family of my fictional character, Junior. Dad blue eyes were open. He’d look around and would seem to make eye contact. His hands, those strong, machinist’s hands, would squeeze my fingers. Some in my family believed that Dad communicated with us in his own way. For me, his responses were random, not resulting from conscious effort. Dad lingered for months on life support before his organs gave out and he passed away. Letting him live like that wasn’t my choice, but I wasn’t the decision maker.

When I’d go to visit Dad, I would have trouble breathing from the moment I entered the small community hospital. Still, I preferred to visit him by myself. That way I could be part of his silent world, sit beside him, read to him, and whisper into his ear. I thought he might be aware of me on some level. Who knew for sure? My aunts had left books on his nightstand: Chicken Soup of the Soul titles; a book of devotionals. I’d left one of my Detective Nan Vining hardcovers, which soon disappeared except for the book jacket. When I visited Dad, I’d pick up one of the books, open it anywhere, and begin reading aloud… and weeping.

I’d take my mom and my siblings to see Dad as they didn’t want to go by themselves. I witnessed their one-sided conversations with him as they recounted lovely recollections along with regrets and goodbyes. It was like watching a series of one-act plays.

I got to know the subacute unit’s staff and routines. Some patients were more aware and active than my dad. The patients who were able would play with toys and musical instruments. The staff threw theme parties with decorations and costumes for the patients and the families.

I became familiar with my dad’s roommate, a Latino teenager, and his mom a friendly, petite woman in her forties who was there every time that I was there. Her son had nearly drowned in a swimming pool and had been in the unit for years. His body had atrophied, but he could move his head and his crooked arms and legs. Photos on a bulletin board across from his bed showed a strapping and handsome youth. One day, I came into the room and his mom was nuzzling him with a brightly colored, plush toy toucan that played music. The boy seemed to love it, moving his arms and legs like an infant. His mom was laughing and talking to her son as if he were a baby. Weeks afterward, I came into the room and the boy’s bed was stripped and the mattress was rolled up. All his personal items were gone and his bulletin board was empty. A nurse told me that he’d passed away. I never saw his mother again. The boy was my inspiration for Junior Lara and his mother inspired Junior’s mom, Fermina.

During those long months when Dad was in the subacute unit, I didn’t write about my experiences. They were too fresh and too painful. Still, the aloof writer who’s always sitting on my shoulder saw and heard everything. Not long after Dad passed away, I opened a document on my laptop and did a core dump, furiously typing everything I remembered.

Sometime later, I decided I wanted to write a standalone novel, something with a paranormal-ish, horror-ish theme. My experiences with my dad’s final illness, the family dynamics, the subacute unit–all of it–weighed on me. The story begged to be told. Writing The Night Visitor was a long and complex journey. I’m proud of this book. And that aloof writer on my shoulder? She’s always with me, coolly observing and remembering everything.