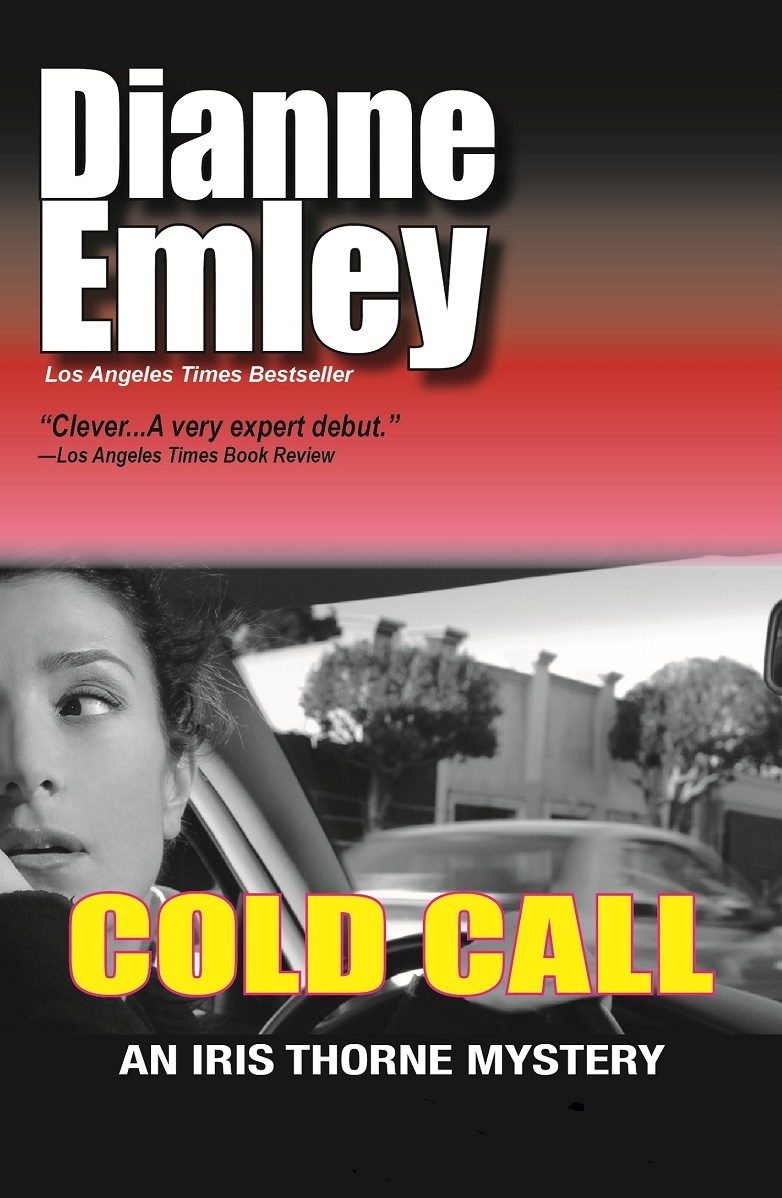

Cold Call

Iris Thorne traded her job teaching the deaf for a career in Los Angeles’s glittering financial district, where the day starts on Wall Street time at 6:00 a.m., and—in the “greed is good” late 1980s—all of life’s questions have numbers for answers.

Big numbers. With her not-quite-paid-for Anne Klein suits and Triumph sports car, which leaks a little oil, Iris is a high-stakes success. Still, the only man at the office who knew the real Iris was Alley, the deaf and handicapped mailman. When Alley is killed, the police insist he was a victim of random gang violence. Iris doesn’t buy it—and Alley’s death has left her with a number of problems. The first is lanky, red-headed police detective John Somers… Iris’s first love, back in her life after twenty years. Then there’s Alley’s secret legacy—a safe deposit box filled with souvenirs and some well-worn items of sentimental value: 238,000 of them, in hundreds, bundled together with rubber bands.

The cops are looking for a killer. Some professional hard guys are looking for revenge. And, for a lost friend, Iris is looking for justice—a high-priced commodity in the L.A. marketplace, where life can be even cheaper than dreams.

— Los Angeles Times Book Review

“One of the best author debuts in many moons… Clever writing, characters shining with individuality… impressive.”

— Cleveland Plain Dealer

Chapter 1

Alley Muñoz walked down the street, stepping heavily on his right foot, swinging the left in a semicircle behind, holding the aluminum briefcase close to his side in his good right hand, his left hand flapping from his bent-wing arm as if he were waving to no one in particular.

Two homeboys at the bus stop jabbed each other as he passed and it occurred to him that they’d been waiting for him. He tightened his grip on the briefcase and made an arc around them, writing off their staring to a stranger’s fascination with his handicap, and continued walking down Lankershim past the clutter of shabby retail establishments like he did every day after work.

He reached the Café Zamboanga, the name “Studio Grill” still visible in faded paint on the brick sidewall. Paper-and-ink posters were taped in the café’s big picture windows. Carnitas. Menudo los Domingos. An old man with his pants belted high around his waist sat at the chrome counter, his fedora at his fingertips, his cane hanging next to him, and watched Alley’s lurching progress outside the café’s windows through clouded blue eyes.

Alley put the briefcase in his bad hand, holding it high and close, and pulled on the heavy glass door with his good right. The door opened half a foot and he wedged his shoulder in, banging the briefcase against the frame before pulling it through. He took off his jacket, picked at invisible lint before he folded it over the back of a stool, and waved his good hand at the old man, who nodded back. He put the briefcase on the floor and slid his foot next to it.

A middle-aged Hispanic woman with thick black hair down the middle of her back and a pink waitress uniform came over to him from behind the counter.

“Hi, Alley. How are you today?” she asked, shouting.

He read her lips. “Fiii.” He nodded, smiling with white, even teeth. A muscle spasm twisted his smile into a grimace, and a glistening drop of spittle fell on his chin. He smoothed his red-and-navy-striped tie with his good hand. “Haa ar ooh?”

“Not too bad. Coffee?” she said loudly, even though he couldn’t hear her.

“Eesss.”

She put a cup and saucer in front of him, the glaze shattered with spiderweb cracks, and filled it. Alley sipped and glanced at a Spanish-language newspaper that was on the counter.

“How’s your mother?” the waitress asked.

Alley looked at her quizzically.

“Your mother? Tu madre?”

He nodded. “Eessss.”

The waitress shrugged at the old man, who shook his head.

Alley saw and continued sipping his coffee. He rubbed the side of his polished loafer against the aluminum surface of the briefcase. He emptied the cup and pulled two dollar bills from a black leather wallet and put them on the counter.

“Thanks, Alley. Hasta mañana.”

He nodded and walked out onto the crowded sidewalk. Beads of perspiration formed on his forehead. It was still ninety degrees at 5:00 in the evening but he put his jacket on, setting the briefcase near him on the sidewalk.

Alley watched one of the homies from the bus stop walk toward him, his stride as precise as a march step, one arm swinging behind his back then in front, each shoulder lowered in time. His khaki pants came down low over his bright white Nike tennis shoes, and he wore a too-large, plaid, wool flannel shirt buttoned to the neck, in spite of the heat, the long tail trailing behind. His chin was cocked up and a cigarette was wedged behind his ear. He walked up to Alley and put his hand on his arm. “Hey, ese. You got a match?”

Alley smiled and a muscle spasm twisted his mouth. He pulled open his left jacket pocket with his good hand and looked inside.

Alley was shoved backward. He took his hand from his pocket and looked at the spreading red stain across the front of his shirt. He dropped the matches on the ground. He felt the pressure again, then looked up to see the ice pick come toward his chest a third time.

Alley screamed.

The boy watched him, his face serene and curious.

Alley screamed and screamed. He pawed the air and wailed the same note over and over. He staggered down the sidewalk, throwing his right foot forward, swinging the left behind.

The boy was already turning the corner onto a side street by then, running fast.

Some people ran after the boy and some watched Alley, not knowing what to do. There was so much blood.

Alley dropped to his knees, his breathing short. He fell back onto his good arm, then onto the sidewalk, his legs contorting under him. He screamed again and again, his tongue churning like a landed fish.

The waitress ran out of the Café Zamboanga and kneeled beside him. Alley tried to speak, but his tongue just flapped in his mouth. Then he died.

The waitress walked back to the doorway of the café, rubbing her bloody, trembling hands on her pink uniform. She shrugged her shoulders and moved her lips, telling herself there was nothing she could do, and then she saw the briefcase on the sidewalk. She pulled the handle. It didn’t move. She got a better grip on it and picked it up, leaning to one side with the weight, and took it inside the café.

“Take it to his mother… pobrecita… that poor woman… pobrecita, pobrecita.